The Ultimate Guide to Pasture-Raised Meat, Regenerative Agriculture, Sustainable Eating, And Why You Should Vote With Your Fork

When it comes to the cost of regeneratively farmed and organic food, it’s no longer a case of ‘can I afford it’, but rather ‘can I afford not to?’. The answer, when it comes to our health and the health of the planet: is a resounding no. There is no other option when it comes to the sustainability of our soil, of our health, and of our continuation as a species on this planet. If we want to keep living on this earth, we have to take a good hard look at the way that we farm, realising that our food systems and the way that we manage animal production can be our greatest enemy or our greatest ally: depending if we farm against or in tune with nature.

Today we will explore the in’s and out’s of how food is grown, and explore the meaning of some of the common words being thrown around in the realm of agriculture and meat production. Hopefully this will give you some insight to make informed choices regarding your food, and the role that it plays in creating the world that you live in.

Disclaimer: I am not a soil scientist, and actually my dive into the world of regenerative agriculture is relatively new. I’ve been immersed in this world slowly over the past decade, but only very recently have I started volunteering on a regenerative farm, awakening to how truly important this subject is. Despite having a lot to learn myself, I’m sharing what I do understand now, because most people have little to no information about the regenerative agriculture movement.

The movement itself is as old as time (based on nature!) and yet it’s oddly new to the farming world, at least in the advent of the industrial agriculture revolution. Although I am relativly new to this subject, I feel deeply that it is something so viscerally imbedded in all of us; a truth that just flows up from the soil and into our human bodies. I can hear the soil crying out: this is the answer. And so I have really no other option but to become an advocate for it. As a writer in the health industry, I can see no other subject as important as the plight of regen ag. Consider this article to be a gateway, a seed if you will, for your own exploration into the world of sustainable eating, regenerative agriculture, and the importance of investing in food raised in these techniques.

“Our body is essentially soil and water. The quality of our soil will determine the quality of our food, our body, and our life.”

— SADHGURU

ORGANIC VS. GRASS-FED VS. GRASS-FINISHED: THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO PASTURE-RAISED MEAT, REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE, SUSTAINABLE EATING, AND WHY YOU SHOULD VOTE WITH YOUR FORK

HEALTH AS A SPECTRUM

Now it’s important to note that ‘health’ is undoubtedly a spectrum. There aren’t two categories of “good” and “bad” when it comes to anything in life, and the grey area definitely applied to the meat and regenerative agriculture industries as well. I’m not trying to shame any one type of practice, nor should you ever feel guilty for having made certain choices in the past (or future). But the way we eat is, in my opinion, the single largest way we vote for the kind of world we want to live in, so making informed choices is absolutely crucial.

The concept of regenerative agriculture itself isn’t clearly defined, but what I do know is that it’s about doing better by our agricultural practices. What this means for you is making informed choices regarding your food; taking strides to better your own health and that of the soil as a result of that. When we know better, we do better.

VOTE WITH YOUR FORK

Every time you buy something to eat, you vote for the kind of world you want to live in. This may seem like a grandiose statement, but when you work your way back along the whole chain of production between what’s on your fork and the way it got there, you’ll realise that indeed the food that we eat paints a clear picture about our values on this planet.

There’s no opting out when it comes to this kind of election, it happens every time you chew. The food you buy directly impacts the whole ecosystem, and has very real consequences in terms of how the history of our civilisation will play out. In the age of information, ignorance is no longer an option.

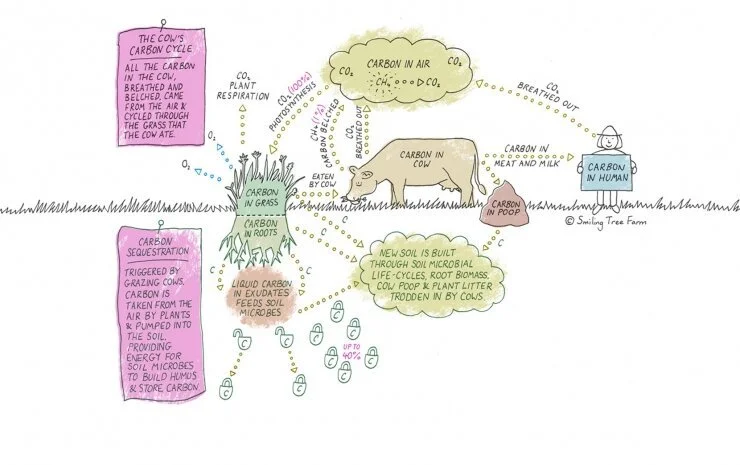

Image source: unknown.

We’ve been so disconnected from our food that many people don’t know the first thing about food production. The disconnect between food and table and the commodification of food divorced from soil health had led us down a path of diseased and disenfranchised humans. Reconnecting with my food all the way down to soil that it is grown in has been one of the most empowering and awakening experiences of my life. My wish is that this article helps spark the same desire inside of you, to claim your power and start making better choices.

“Regenerative is the lens through which we have to look at everything we do on the planet in the future.”

— MICHAEL BESANCON, CEO BESANCON GROUP

IT STARTS WITH SOIL

The quality of your food depends on a few things, but it starts with the soil. Healthy soil depends on its structure, its chemistry, and its biology. Healthy soil is alive, it is a thriving ecosystem of microbes, bacteria, and fungi. Healthy soil has deep root systems that leaves space for airflow and life but has structure and strength thanks to humus and organic matter. It retains water for times of drought. It is full of life and death, the latter feeding the former. Healthy soil is abundant in minerals, it contains calcium, carbonates, magnesium, phosphates, sulfates, potassium, nitrate, ammonium and iron— all in a delicate balance. These nutrients (or lack thereof) reflect in the food grown in the soil.

For soil to thrive in the world of agriculture, it has to be managed very mindfully. The practices that arose during the industrial agriculture boom of the 19th century completely ignored the wisdom of nature and ditched the ‘give and take’ principles for a ‘take and take some more’ mentality. These practices led to mono-cropping, especially to feed the livestock that was now living on one single paddock. Mono-cropping led to a narrowing of the biodiversity of the land. An eco-system requires a variety of plants, fungi, bugs, and animals that work together synergistically: feeding one another and keeping the whole system in balance. With only one crop, we saw the quick demise of diversity not only above land but below it as well.

Mono-cropping met the likes of hybridized grains, and GMOs, which further decimated the biology of the soil. With a lack of diversity of the ecosystem came a vulnerability to invaders like pests, and weeds. To get rid of them, these ‘modern’ farmers introduced pesticides and herbicides, which was the nail in the coffin when it comes to soil health.

What used to be an ecosystem feeding and supporting itself through cycles of life and death became one of domination by the farmer. In our efforts to produce more output, we totally broke down the cyclical nature of nature and before long were faced with the various problems of modern-day agriculture; notably: very little profit (too many costs involved), high carbon emissions (vs. carbon sequestering), and dead soil.

“We stand, in most places on earth, only six inches from desolation, for that is the thickness of the topsoil upon which the entire life of the planet depends.”

— R. NEIL SAMPSON

CARBON 101

If you’ve turned on the news in the past 5 years, odds are you are at least somewhat aware that we have a carbon problem on the planet. The key thing to remember is that: carbon is not the enemy. In fact, without carbon, we wouldn’t be alive! Carbon is one of the key building blocks of life. It makes up much of the matter on this planet, and the problems we are facing is that there is an imbalance of carbon: too much in the air, and it’s warming up the atmosphere.

Global warming and cooling is indeed a natural phenomenon, but the issue is that these cycles generally take a really long time. Carbon is naturally excreted into the atmosphere, in a few ways. It comes out of volcanoes, its exhaled from our mouths (co2, carbon dioxide), it’s cow farts, and it’s decomposing bodies: carbon is a natural part of the cycle. The keyword here is cycle. When carbon cycles, all is well. Think of it this way: we breathe in oxygen and we breath our carbon dioxide: neither are innately bad. However, if we had only o2 or only co2, we would be in trouble. The cycling is what keeps everything in balance, and when it comes to carbon, a key aspect of this cycling is carbon that is in the atmosphere vs. carbon that is stored. Stored carbon is often referred to as a ‘carbon sink’ a concept I’ll elaborate on a bit later on.

With the advent of the industrial revolution, however (the invention of cars, big machines, big cities, etc), we have disrupted this cycle. By capitalizing on carbon-based energy sources (fossil fuels, coal, and oil) to build our modern society, we have tipped the balance of air-bound vs. stored carbon because burning these carbon bonds that were stored in the earth for energy, we are releasing more carbon into the air than we are sequestering (storing).

When fossil fuels are burned through combustion, they release their carbon as heat (energy) and any impurities as emissions. This causes accelerated temperatures because carbon stores heat. So too much carbon in the air elevates the temperature of our earth’s ecosystem, which melts the cold stuff, and eventually, this leads to ‘global cooling’ (historically, we don’t do too well in Ice Ages…).

THE “CARBON SINK”

The concept of the carbon sink became widely known following the UN’s 1992 Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty that addressed our collective concerns about the man-made co2 emissions and their impact on global warming. Now whether or not you ‘care’ about global warming or climate change, I urge you to read on, because this article is as much about saving your own health right here and now, as it is about saving the planet. The key here is soil health, and the soil grows your food, it feeds you, it creates you. You can see carbon sequestering as the ‘goal’ or simply as a bonus of soil health, of regenerative agriculture, of growing nutrient-dense foods. But it’s all one and the same: the ecosystem requires carbon to cycle, and storing carbon underground (in the soil and oceans) is the most efficient and beneficial way to do it (unless you want to start holding your breath all the time).

Back to the carbon sink: essentially plants (trees, grass, etc) are our key to sequestering carbon from the air and locking it in the soil. This happens because plants photosynthesize energy from the sun to take CO2 from the air, split it into carbon and oxygen, release the oxygen back into the air and use the carbon to grow. Photosynthesis is the key to storing carbon in the soil, which is why cows are actually crucial to turning our lands into carbon sinks. When they are managed intelligently, cows can graze on grass in a way that ebbs and flows just right to continuously promote photosynthesis.

You can essentially think of photosynthesis as carbon sequestering.

Plants breathe in carbon dioxide (co2), they keep the carbon, and they breathe the oxygen back out.

“We have to have regenerative food, farming, and land use if we hope to survive.”

— RONNIE CUMMINGS, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE ORGANIC CONSUMERS ASSOSIATION

IT’S NOT THE COW, IT’S THE HOW

Cows have often been linked to the problem when it comes to carbon emissions, which doesn’t tell the full story. Cows can be a part of the problem but they are also they key to the solution. It’s not the cow, it’s how the industrial agriculture revolution (humans) took them out of their natural herd-based grazing patterns, and plopped them onto one single paddock. The problem is not cows, it’s how humans have managed (or failed to manage...) them. This topic is a big one, but it can also be understood fairly simply.

ROTATIONAL GRAZING

When cows and ruminants naturally and freely graze in herds, it creates a sort of pattern. They mow down on one area, and move on. When they move on, the grass is given time to rest, which means the roots that were disrupted by the grazing decompose into the soil, which feeds the biology of the soil. The root disruption also creates air, which promotes healthy soil structure (less susceptible to erosion). Since the cows have moooo-ved on (sorry, I had to), the grass is also given the chance to re-grow, which as it grows sequesters carbon from the atmosphere and brings it down to the roots, and eventually that gets stored in the soil. Birds naturally follow ruminants in nature, their pecking and digging disperses the cow pats (poop) left behind by the ruminants, which fertilises the soil and sequesters even more carbon whilst nourishing the soils biology and balances its chemistry (cow poop is full of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium). The chicken add in their own excrements to the mix, and there you have it: healthy, nutrient-dense and alive soil. Zero human intervention.

THE IMPORTANCE OF ROTATIONAL GRAZING AND HOLISTIC LAND MANAGEMENT

When we started farming for food (ie. not hunting and foraging in the wild), things inevitably had to change. The ruminants that grazed naturally on rotation we started raising ourselves, using a ‘set stock’ model that kept cows, sheep, pigs, and other animals on one fixed piece of land that they would continuously graze upon. We started planting the seeds of wild foods in areas we could manage ourselves, harvesting and eventually started selling on mass-scales. This worked for a while, because there was so much land. When one piece of land lost its fertility, we moved onto the next. Unfortunately (or fortunately) this is no longer an option. We are running out of fertile land, and so it’s time to start examining our agricultural processes and re-connect to natures wisdom.

Not every culture has disconnected, by the way. Many poor villages (either poor in resources or land, but often both) have maintained this ancestral honouring of the land. It’s from some of the places in Spain, in Greece, etc, that we see some of the worlds best food production to this day. Quality soil supported by regenerative farming practices means delicious food.

Reconnecting to ancestral patterns, for those of us who have lost our way, means implementing holistic land management. Managing the land holistically means seeing the short term and long term impacts of our decisions, it means considering what's going on above soil and below. It means looking at the micro and the macro.

For too long, modern agriculture has looked at food as a commodity for profit with the mentality of “how much money can I get out of this food, as soon as possible”. The get rich quick mentality is what had led to burning carbon to the rate that we have, to mono-cropping foods soaked in poison (herbicides and pesticides), to using artificial fertilisers, to feeding ruminants grain and stock setting (continuous grazing of a single paddock).

This photo taken by Andrew from Byron Grass Fed shows the stark difference between two paddocks, in the heat of the recent 2019-2020 Australian drought. The land on the left is the holistically managed Conscious Grounds farm in Myocum, and the rotational grazing practices effectively stored enough water in the top soil to keep the land completely covered and even alive. The right is a neighbouring farm that practices set stocking (continuous grazing). The bare soil and dehydrated grass is a direct reflection on the over-grazed practices of the farm.

QUICK RECAP

Healthy soil:

More ground cover

More roots

More carbon stored in the soil

More water retention in the topsoil

Recovering groundwater levels

Less erosion

More biodiversity

Less carbon in the atmosphere

More natural food (grass) for ruminants, less reliance on exogenous inputs to feed animals, and healthier diets means healthier quality of food for the community

Depleted soil:

Less ground cover

Fewer roots

Less carbon stored in the soil

Less water retention in topsoil

More erosion

Less biodiversity

More carbon in the atmosphere

Less natural food for animals, more reliance on exogenous sources of food for animals (and more carbon in the air to produce such foods), which is generally an unnatural diet, resulting in sicker animals and less nutrient-dense food for the community

Problematic soil leads to an imbalance in the ecosystem, more weeds, and poor quality soil which leads to more inputs like herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers— which further degrade the soil and root systems of plants

When we fail to manage the land holistically when we interrupt nature’s patterns: cows graze the grass without rest in a single paddock. Set stocking without rotation and resting the grass keeps it constantly short, which means a weak root system, compacted soil, little to no biological diversity in the soil, grass that is more susceptible to drought, and ultimately cattle that is fed grain (an unnatural diet that leads to sicker animals, and less nutrient-dense food). The grain requires mono-cropping (another soil killer) that is often GMO grain, which requires industrial processing (hello, carbon) and often comes with a healthy side of toxic herbicides and pesticides (like glyphosate).

Cows from regenerative farms = carbon sink.

Cows raise à la industrial agriculture (or worse: factory-farmed) = destructive for the soil, for the animals welfare, and your health as a consumer.

Carbon cycling with rotational grazing.

Image by Smiling Tree Farm.

RUMINANTS FOLLOWED BY BIRDS: BIOMIMICRY

Not all regenerative farms have chickens, but I thought I’d touch on it because I personally love this topic. Have you ever noticed how in nature birds are always near grazing animals? Water buffalos and elephants have Oxpeckers, cattle often followed by Cattle Egret, European Starlings on bison— this is the magical symbiotic nature of a biodiverse healthy ecosystem in its full glory.

Birds feed on the ticks and flies that these grazing animals pick on on their journey. Which keeps the animals healthy to start, but also helps spread around their poop to fertilise the land. The birds eat larvae and bugs in the poop, scattering it around and further disrupting the soil (nature’s tillers). As the ruminants move on, the soil it left to rest, regrow, and absorb all the nutrient-dense poop left behind.

On farms, this is emulated (biomimicry) by letting chickens on the land after ruminants have gone through.

European Starlings sitting on Bison.

Image: National Wildlife Federation.

Yellow-billed oxpeckers sit on the head of a water buffalo.

Image: Beverly Joubert NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC.

GREENWASHING

As people make strides to eat healthier, more ethically-raised meat and produce— the rise of ‘greenwashing’ in the food industry has taken off as well. Greenwashing is the use of tactics to make a product appear healthier or natural, as a marketing tool. Unfortunately, the consumer is often left confused when it comes to making the best choices because of a lack of regulation and/ or transparency by producers.

An example is the word natural, that is thrown around to trick consumers into thinking their food products (and cosmetics) is healthier than it it. Factory farmed Tyson chickens are fed GMO grain, treated with antibiotics, and injected with a salt water solution to plump them up, and yet their label promotes “All Natural” chicken. What a joke.

Natural?

Vegan “meat” is another great example of this: we see it labeled as healthy, with smiling cows. But when you break it down, what is healthy about a patty made from soil destroying mono-cultured GMO crops, highly processed vegetable oils, imported products manufactured in a plant that burns carbon for energy. Who is this good for? It destroys the ecosystems in which the various ingredients were grown, it requires multiple carbon-producing inputs, it creates highly processed, packaged, nutrient-deficient fake food that is making humans sick. If I was a cow, that would make me anything but happy. Factory farming would too, which is why we have to take it back to “it’s not the cow, it’s the how”. We have to empower ourselves with information to ask the right questions and make the ethical, more sustainable choice.

When farmer’s market stalls offer a HUGE range of perfectly-looking fruits and vegetables, odds are they are not from a farm and are actually just re-sellers. Here you can see the produce still has stickers on it… The produce in this case is no different than your big-chain grocery stores. Lies, charged with a premium.

Greenwashing also happens at your local farmers markets. It’s not uncommon for stalls not to actually represent a single farms, but rather individuals ordering wholesale and selling at retail price. They remove stickers, pop the produce in crates, and charge you a premium to feel good about yourself.

This is why it’s so important to know which questions to ask, and what to look for. Reading a label at the supermarket is unfortunately not going to give you the truth, most of the time. Getting the truth requires a little more digging, a little more reconnecting. A little more time.

When farmer’s market stalls offer a HUGE range of perfectly-looking fruits and vegetables, odds are they are not from a farm and are actually just re-sellers. Here you can see the produce still has stickers on it… The produce in this case is no different than your big-chain grocery stores. Lies, charged with a premium.

Most people live in a time-poor lifestyle, always busy, always on the go. But you have to realize that we always make time for what matters to us. Putting food as a priority is no longer an option. Once you’ve spent the initial time making those connections and asking the right questions, you can make confident choices when it comes to the food that you eat. Whether you’re doing it for your planet, for your health, or for the health of your children: take the time. Reconnecting with your food reconnects you to the earth, to yourself. Something really special happens when you decide that you are no longer just a target for marketing companies when you decide that you will actively participate in shaping the world that you live in. Informed consent requires more accountability, but the empowerment that comes from it transcends diet alone. It empowers every aspect of your life, it’s what makes you human.

The text below will start you off, but remember: you hold the key to making the real connections within your community. You have to take the information below and start asking the questions. You have to start shaping the demand, by raising the standard of your purchases, by refusing to support industries that are decimating our soil and abusing our microbes, our fungi, our plants, our animals. You vote with your fork, whether you like it or not.

BREAKING DOWN THE BUZZ WORDS

SUSTAINABLE

I’m going to keep this one short, although I feel I could write an entire book on the nature of this very word. I think we need to see sustainability (like health) as a spectrum, because for the most part, almost nothing humans touch is actually “sustainable”. Farming by its very nature is manipulating, which means we are undoubtedly interfering with the long-term balance of nature that defines sustainability itself. That being said, the more we strive to align ourselves with natures patterns (biomimicry), the more we lean into the long-term viability of our decisions.

A good way to see sustainability is by observing/ taking what is given to you as opposed to manipulating with preference. When it comes to eating, this means getting used to eating in season and what grows locally. The more we select (our favourite vegetables, our favourite cuts of meat) the more we create an imbalance in the supply chain, the more we drive prices wars, the more waste we create, the more we force farmers to farm things that go against what should be growing (more on this later).

“After 3.8 billion years of research and development, failures are fossils, and what surrounds us is the secret to survival.”

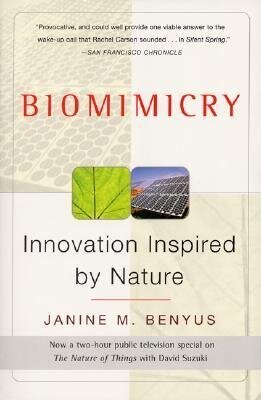

— JANINE M. BENYUS, BIOMIMICRY: INNOVATION INSPIRED BY NATURE

LOCAL

Local is a term that should denote that the food comes from nearby, but unfortunately there is no rules when it comes to throwing around the term “local” and some companies use it so loosely it hurts. Local, to some, could be anywhere within the same country, or same continent. Realistically, in my humble opinion, something that came from one side of the country and was flown to the other, is not local.

So when it comes to “local” I suggest asking specifically what farms your food is coming from. From there, decide if local is indeed local. A good measure stick for something being truly “local” would be asking yourself if you would consider driving to that farm yourself to get your food. If not, well, probably not very local is it.

Local food matters because it impacts two key things. For your health, we’re looking at the most prana or life force in your food. Real food loses life force, it decomposes. The closer you get to your food, the fresher it is, the more nutrients you get to consume. Did you know that most (if not all) imported foods are picked prematurely, to allow them to ripen on the way? This is problematic because not only is it losing nutrient density on that plane ride, truck ride, and sitting in storage at your local super market; but more importantly it never got the chance to ripen still connected to the soil. Think of it like growing a baby to term 10 months in utero, vs. having a premature birth at 4 months and being kept in the ICU on a feeding tube.

You want a baby to come to term in utero, and you want your food to ripen in nature. The latter is only possible if the food itself isn’t being shipped far and wide. Eating local drastically increases the odds that your food ripened in nature and is still fresh.

GENETICALLY MODIFIED ORGANISMS (GMO)

A GMO, or genetically modified organism, is a plant, animal, microorganism or other organism whose genetic makeup has been modified in a laboratory using genetic engineering or transgenic technology. To date, there have been no long term studies investigating potential effects of GMO food on human health. Most of the research used to claim that GMOs are safe has been performed by biotechnology companies. Animal studies highlights organ damage to the animals that are fed GMOs – gastrointestinal and immune disorders, accelerated aging, reproductive organ problems, infertility, lesions and inflammation, altered blood biochemistry, altered gut bacteria, tumors, cancer, birth defects, and premature death.

GMOs are particularly concerning because there’s no ‘undoing’ their damage. Once they are introduced to an ecosystem, them spread, oftentimes outside of the jurisdiction of the farm on which they are used. Unlike chemical pollution, there’s no ‘cleaning up’ GMOs, they can infiltrate organic environments and contaminate the gene pool. This is very scary.

The cherry on top is that GMOs were engineered to be used alongside herbicides, particularly glyphosate (commonly Roundup, produced by Monsanto, now owned by Bayer, a pharmaceutical company). This highly toxic, proven to give cancer herbicide does not affect the GMO crops, so farmers can spray their fields in literally inhumane amounts without killing their crops. More is added to facilitate the harvest of certain crops like wheat (you’re not allergic to gluten, you’re being poisoned by glyphosate), and you’ve got the perfect storm for dead soil.

GRAIN-FED VS. GRASS-FED VS. GRASS-FINISHED

So the term ‘grass-fed’ is a great stride in the right direction when it comes to quality food, but unfortunately it’s a term that has is also slightly (/very) deceiving. Just because a ruminant is being sold to you as ‘grass-fed’ does not mean it was fed grass for the entirety of its life. Most ruminants are grass-fed for a degree of their life, and the use of the term grass-fed is thrown around without much context.

In Australia, for a ruminant to be considered ‘grass-fed’ it cannot be fed grain for more than 60 days, meaning it can be fed grain up to 60 days.

In Canada, a cow must be fed herbaceous plants that can be grazed or harvested, including grass, legumes, brassicas, tender shoots of shrubs and trees, and cereal grain crops in the vegetative state for only 75% of their life.

In the USA the USDA actually revoked the “USDA Grass-fed” label or claim in January 2016, so it’s a bit of the Wild Wild West out there when it comes to the word ‘grass-fed’. There is no standard in the US, and approximately 95% of the cattle in the United States continue to be finished, or fattened, on grain for the last 160 to 180 days of life, on average. That’s a lot of grain.

The common feed for the animals when not grass-fed includes wheat, corn, and soybeans— commonly genetically modified foods that are grown mono-cropped, with an absolutely detrimental impact on the soil and potential ecosystem of that land.

Grain fattens up cows quickly, which is economically profitable in the short term— but this unnatural diet also turns good fat into bad fat. The healthy Omega fats become imbalanced shifting from Omega 3’s to Omega 6’s, which as humans generates inflammation in larger quantities whereas Omega 3’s have the opposite (anti-inflammatory) response. It only takes 30 days on grain for this shift to happen.

Generally, there is a connection between grass-fed/ finished and rotational grazing because the principles of rotational grazing ensure there is higher quality soil, that grows healthier (more nutrient-dense and drought resistant) grass. When grass-finished beef is paired with holistic management (rotational grazing) we have happy cows, healthy soil, nutrient-dense food for the community.

ORGANIC

What organic food is: food produced without the use of toxic chemicals (poison), that have otherwise become the norm with conventional farming methods. Organic food contains no synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, or herbicides— all inputs that are detrimental to soil health (biology, chemistry, and structure).

What organic food isn’t: So although certified organic food pledges not to use chemical-based pesticides or fertilizers, it doesn’t in fact guarantee nutrient-dense food, or that the practices aren’t detrimental to soil health/ the ecosystem. Organic alone doesn’t ensure that farmers treat the farm like an ecosystem.

This explains the potential problem with only organic (without the regenerative component). Organic alone doesn't mean that the soil is cared for. If we simply feed the plant organic fertilisers, we bypass the cycle that sequesters carbon in the soil, the exchange of carbon for nutrients that occurs when we let the SOIL feed the plant.

Organically grown crops could be rows of mono-cultured annual corn crops, being fed certified organic liquid NPK fertilizer, causing soil depletion, shallow roots, imbalanced ecosystems, and ultimately yielding relatively low nutritional value food.

With animal crops, you could be raising cows in factories and feeding them organic grain. The beef would be considered “organic” even if it was locked indoors eating an unnatural diet for its entire life. Organic, unfortunately, does not paint a full picture when it comes to food.

Some of the most regenerative, holistically managed farms I have visited cannot be considered “certified organic” because they use practices like fly tags. These fly tags contain an insecticide that helps keep flies out of the cow’s faces, preventing tick bites, and bugs that can bite the animals aggressively. The tags also prevent the animals from losing so much weight (the energy used swatting away flies).

This explains the potential problem with only organic (without the regenerative component). Organic alone doesn't mean that the soil is cared for. If we simply feed the plant organic fertilisers, we bypass the cycle that sequesters carbon in the soil, the exchange of carbon for nutrients that occurs when we let the SOIL feed the plant.

Image by AgZaar.

So, as you see: organic isn’t as simple as it may look on a label or sticker. What matters more than organic are the practices upheld by the farmers, and how much mindfulness they put into their regenerative practices. You aren’t what you eat: you are what your food eats. And this trickles down all the way to the quality (structure, biology, and chemistry) of the soil it’s grown in.

BIODYNAMIC

Biodynamic agriculture are farming principles rooted in the work of philosopher and scientist Dr. Rudolf Steiner. Similar to organics, biodynamics operate on a no-toxic input rule, but the ethos runs much deeper and includes a recognition of the spirit in nature. The principles and practices of biodynamics acknowledge the ecosystem as a living organism. Biodynamic farmers and gardeners work to nurture and harmonize these elements, managing them in a holistic and dynamic way to support the health and vitality of the whole.

When it comes to our current labeling system, without wanting to create a ‘hierarchy’ per se— because it’s much more complicated than that, but biodynamically grown food is generally top quality. Some of the biodynamic principles go above and beyond what some regenerative agriculture farms wish to or can realistically implement. Not all regen ag farms are biodynamic (and some even consider it almost a cult). Indeed it is a culture, a way of seeing the world and navigating it— it’s quite a magical realm and if you’re into sustainability, delving into the works of Steiner is a must.

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE

This first 2 minute 35 video below explains regen ag very well. Note that this certification is in the works, but there are many many many farms that manage their land holistically using regenerative farming practices that are not certified. Divorce yourself from the idea of a certification, and focus on the message of that regen ag video.

I have to note too that the concept of regen ag is pretty new and relatively undefined. This certification in the video piggybacks on the organic cert, but many people don’t believe a farm has to be certified organic to be regenerative. The second video is a bit longer, and features a famous regen farmer Charles Massy, in Australia. It’s a beautiful story about his work in restoring the health of his lands ecosystem through these regenerative principles.

Although I do eat organic, the more significant issue personally is the quality of the soil and the actual practices of the farm. To me, regenerative agriculture sees their farm as an ecosystem, and they make decisions for the short term and long term viability of the land (above and below it). For example, if fly tags are used on cattle (to keep flies and ticks away), the animals cannot be considered certified organic, even if the entire property contains no pesticides, herbicides, or fertilizers. So the answer isn’t black and white. You have to actively participate in the choices of your food, and not just blindly relying on a label.

Conventional farms are stock managers, they see the animals and crops as commodities, and the mentality is “how can I make the most profit from this item”. Regenerative agriculture farmers are land managers; they ask themselves, “what can I do to protect the natural cycle of this ecosystem, and produce food in tune with this natural cycle.”

“Nature wants a smorgasbord of many many different animals and plants and microbes operating together to create harmony, which restores the health of your land.”

— REGENERATIVE ORGANIC CERTIFICATION

LOW INPUT FARMING

Another way to look at regenerative agriculture is to look at the inputs vs. the use of nature’s cycles (biomimicry) on the farm. When there is large biodiversity on the land, when livestock is managed properly when cover crops are used effectively when the land is given adequate time to rest— the system essentially feeds itself. For example: instead of using artificial fertilizers, cow pats and chicken poop by animals led through with rotational grazing practices will fertilize the land naturally. By letting the soil rest with rotational grazing, the animals can rely on the food supply of the land, which means no need to grow mono-crops to feed the animals, plus all the machinery and processing inputs required to grow mono-crops. By keeping balanced healthy soil, and planting companion plants that work synergistically together, no need to use toxic pesticides and herbicides.

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE Q&A

ARE THERE STUDIES THAT HIGHLIGHT THE DIFFERENT NUTRITION DIFFERENCES BASED ON DIFFERENT QUALITY OF SOIL?

Yes! In a few different ways. There is a device called a Brix refractometer, that calculates the total suspended solids of a plant. Correlating TSS to nutrient density has its pros and cons, but you can learn more by clicking HERE. Lab testing is also a common way to assess other aspects of the nutrient density of foods based on how they are grown, like comparing the nutritional profile of grass-finished vs. grain-finished cattle. THIS study highlights the nutritional benefits of grass-finished, but there is a lot more information online.

In general, I try to get people to move away from ‘science’ as their ‘answer’, because I truly believe in the divine innate knowing when it comes to the Truth. We don’t have to make it so complicated: you know that your health is directly correlated to the nutrients you consume in your food, right? Why else would you ask the question! We need these nutrients to thrive (/ survive, hello scurvy). But where do you think these nutrients come from? THE SOIL. You aren’t what you eat, you are what your food eats: all the way down to the microscopic micronutrients that make up the soil in which the food itself grows.

Minerals don’t come out of thin air (ok, TECHNICALLY if you go back far enough you can argue that the carbon sequestered from the air is required for the exchange of nutrients to grow the food.. hah!). But the principle is that the soil quality = the quality of the food, there’s no other way around it.

Soil quality is tested using very advanced practices (testing pH alone is absolutely not indicative of soil health). There are companies like Soil Food Web that are analyzing soil structure, biology, and chemistry (the 3 legs of soil health) to give an in-depth understanding of soil quality.

Also the most legit badass farmers will be able to tell what’s lacking in their soil just by examining their land (the weeds growing, the quality of their crops, the pests) because these ecosystem imbalances tell the story of the soil imbalances. It’s Jedi stuff, that totally blows me away.

YOU also have the ability to bypass all the fancy testing and harness the innate knowing of your taste buds. I’ve eaten many organic carrots in my time, and sometimes they taste amazing— other-times like garbage. That’s the power of lively, healthy soil. Food grown in healthy soil that was not harvested early to ship internationally— it tastes incomparably better than food grown in nutrient-depleted soil or harvested unripe to ship internationally.

This book is a non-negotiable read for anyone even remotely interested in the quality of food and the future of food production.

Although there is a way to measure quality of food (nutrient density and ratios of things like Omega 3 to 6’s) I urge you, to see the issue of regenerative agriculture more holistically. The quality of food is almost a bi-product of the mission to save our land. Yes, the food tastes better, it is more nutritionally dense, but if we fail to farm in this way, we will eventually degrade the top soil to the point where we can no longer grow food, period. The way we currently manage animal farming is also inhumane, especially in the US factory farming setting. So yes, grass-finished meat is healthier but don’t divorce that from the whole picture: regen ag grass-finished beef cares for the soil, for the animal welfare, for the air quality, it supports the whole ecosystem, and we are a part of that.

HOW DOES REGEN AG DIFFER IN DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTS? (TROPICAL, ARID, TUNDRA, TEMPERATE)

This answer could fill out an entire encyclopedia, and I absolutely do not have the answer— because not only does the regen ag farming practices differ from climate to climate, they also differ based on microclimates (which can change from farm to farm within one same region). The thing about holistic land management is that it requires an individualized approach. There is no textbook for what type of inputs you will need, how many cows, how much land, how often you should rotate the cattle, how the property should be divided— it always depends. And the answers you get one year might not work next year. This is the nature of regenerative agriculture: its nature led, it oscillates, its individualized. It requires observing the ecosystem of that area instead of trying to dominate it. So, there is no simple answer to this. It would take me many lifetimes to acquire the experience to start answering it specifically, and even then, I would say: it depends.

IS IT POSSIBLE IN A NORDIC CLIMATE?

Yes! Not only is it possible, but using regenerative practices helps support the resilience of the ecosystem in colder harsher months. I suggest watching the video below, that depicts the wonders that regen ag can have on farms located in nordic climates (this farm is in northern Alberta, Canada… with -30 to -40 degree Celsius winters). They’ve also had the quality of their food tested, yielding incredible results.

I also love the video below, that shows a family building an urban permaculture homestead in a cold climate. Gotta love Canadians!!

DO YOU BELIEVE IT’S FEASIBLE FOR EVERYONE TO EAT THIS WAY?

Absolutely. The supply will match the demand when the demand comes. This means the consumers have to start speaking up and demanding that their ruminant meat be 100% grass-fed and grass-finished. Buying produce in season, from local regenerative farms. It means the consumer has to start asking the right questions to shift the farming practices, which can actually happen quicker than we think.

“Farmers as entrepreneurial business people will move their production model to a model that pleases that consumer. ”

— WILL HARRIS, FARMER AT WHITE OAK PASTURES

In fact, I don’t only think it’s feasible, I think it’s the only solution if we want to survive as a species. Infertility of the soil means infertility in humans, as above, so below.

HOW CAN I BUY LEGITIMATELY REGENERATIVELY FARMED MEAT?

So there is a regenerative organic agriculture certification, that piggybacks on organic and even the fair-trade certifications. It’s definitely the mecca of certs, but it’s very new and odds are if you only eat according to the cert you won’t find much at the moment. I’m not even 100% sure the program is rolled out fully. Biodynamic certification would be your next best bet, this is more commonly found across the world. It is not, however, the only regeneratively farmed meat. So all biodynamics are regenerative but not all regenerative is biodynamic.

Either way, your best option is no doubt to connect directly with farmers. It’s really the only solution. Yea, it will take a little bit of time to ask the questions to your current meat suppliers, or to source out local farmers markets, or make some phone calls. But once you have found the solution, you have it for life.

I want to note that modern-day butchers, for the most part, aren’t butchering anything. They are often salesmen and women and don’t actually have qualms about just telling you what you want to hear. I don’t suggest asking a butcher if the meat is grass-fed and finished, and taking their word for it. Ask, and then follow up by asking the name of the farm(s) that their meat comes from. Call the farm or visit if you can, experience it for yourself and decide if it aligns itself with your understanding of regenerative and your values.

IF WE CAN’T BUY FARM DIRECT, WHAT KIND OF LABELS TO LOOK FOR?

If you had to pick a label, the new regenerative organic certification or a biodynamic certification gives you a good idea of farming practices on holistically managed lands, with healthy soils. That being said not all regenerative farms have such certifications. Aforementioned, you can’t actually trust labels for the most part, especially if they just say ‘grass-fed’ or ‘organic’. So, scroll down to the bottom of the article and check out the “questions to ask” section, and there will be a handful of questions for both produce and meat, that you will probably not get directly answered by the grocery store. Even if they do answer, I suggest calling the companies directly, finding out the names of the farms that supply to them, and asking them the questions. Who knows, you may even be connected directly to a farm (after a little digging) that you can buy direct from.

WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU CAN’T GET TO A FARMERS MARKET? … COLES AND WOOLWORTHS FREAK ME OUT NOW.

For the non-Australians reading this, Coles and Woolworths are big chains, cross-country grocery stores. And they have both recently been stocking grass-fed beef, as well as an organic fruit/ veggie section.

Ok look, first of all, I’m going to be honest, that access to farmer’s markets and/ or buying direct from farms plays a *huge* role in deciding where I settle down for longer periods of time. When traveling Europe, the farmer’s markets are a given, they exist continent-wide, and I was able to shop local, organic farmer’s market across 10 countries with zero problems. They still have it ingrained in the culture, which isn’t always the case in Australia and North America.

So first off, don’t freak out. If big grocery stores are your only option, surrender to that. That being said, make sure that it is indeed your only option. Getting immersed in your community might be the first place to start: ask people at your local health store where they acquire meat. There are increasing amounts of co-ops that source out quality meat (and/ or fruits and veggies) and act like small-scale distribution companies to the community.

Next up: try an online search. I suggest looking up keywords like: rotational grazing, grass-fed and finished, holistic land management and also include the name of your area. Now, most farms won’t necessarily have websites. So you may hit a dead end there. But, you can also try “cow share *your area*”. Cow shares are when a handful of people come together and split the cost of a cow, which comes fully butchered and generally frozen. You can’t assume the cow will be grass-finished but they often can be, so inquire. You’ll likely need a chest freezer in this case, because the orders are rather huge.

In the US, there are high-quality pasture-raised, organic, regen agriculture meat delivery services, like Butcher Box. They ship straight to your door. As far as I know, that doesn’t exist in Australia or Canada (yet!)

You may also consider driving a few hours away TO a regenerative farm that sells direct, or a farmers market or legit butcher and just filling up a large cooler, and keeping the goods stored in your freezer. Invest in a chest freezer and take a road trip every couple of months to a place you know you trust, and stock up.

HOW THE HECK DO YOU EAT SUSTAINABLY IN THE MIDDLE OF THE UK WHERE IT’S UNHEARD OF?

Unheard of, according to who?

Hill Top Farm's meat is 100 per cent grass fed, doesn't use antibiotics and the bullocks are raised to four years old Image by Stephen Garnett

Since I started writing and sharing my thoughts on regenerative agriculture, many people have reached out from all over the world saying how hard it is to find high-quality meat and food, when in fact they actually have done very little looking. You can check out THIS article by the Independent, one of the first things to pop up on Google when you type “regenerative agriculture UK”.

The thing about small towns, especially in Europe/ the UK is that many practices are by nature regenerative. Due to lack of resources, old school farmers never took on the practices of industrial farming, with all the added costs and inputs.

Just because you haven’t heard of something, does not mean it’s unheard of.

I suggest reaching out to RegenAG UK (RAUK), a “network come training organization which promotes Regenerative Agriculture in the UK by connecting leading pioneers and trainers from around the world and within the UK with farmers, smallholders, and other interested parties via short courses, seminars, and workshops”.

Hill Top Farm's meat is 100 per cent grass fed, doesn't use antibiotics and the bullocks are raised to four years old Image by Stephen Garnett

I’M LOOKING TO BUY LAND TO KEEP A FEW ANIMALS AND GROW A FEW THINGS— WHAT DO I NEED?

I think it’s problematic to pose this question in passing on an Instagram story (which is where I reached out to the Becoming Fully Human ‘audience’ to get these Q&A questions), and expect ‘the’ answer. Understanding holistic management takes a true investment of your time and attention, it’s a lot of work. That shouldn’t dissuade you from doing it, but to answer this question you need to delve into the world of regen ag, both theoretically (books, podcasts, etc) but more importantly you need to actually show up: on a farm, to a workshop, to a course, speak to farmers in the microclimate you want to buy land in. Volunteer on a local farm, I think that’s the best place to start. Every day I spend at Conscious Grounds I realize how much work is ahead of me if indeed I want to be a true steward of the land.

What you need completely depends on where the land is, how big is it, what the soil conditions are, what the climate is (which in modern-day, requires a constant re-evaluating and adapting). It depends on your resources, on how many people are involved on the land. It requires an understanding of the ecosystem, of soil composition, of what grows natively and in what season. I could go on.

In his book “The Third Plate” Dan Barber interviews a regenerative farmer who says that you should be able to identify every type of grass on your land. Now this isn’t obviously a requirement, but let that concept sink in. Too many people are rushing to do things without understanding the nature of the ecosystem they’re trying to be a part of. Holistic management requires observation, understanding, total immersion, and a type of reverence for the process that I’m only just starting to understand myself.

WHICH FERTILISERS ARE USE IN REGEN AG, IF ANY?

So the thing is regenerative agriculture itself isn’t defined as clinically as other certifications. So, it depends. This subject runs deep and goes beyond my current scope of knowledge, but here’s what I do know:

One of the ‘goals’ of regen ag is to minimize inputs, in favour of using biomimicry (nature itself) to preserve the land and ecosystem. In regenerative agriculture, many things are used to enhance soil quality: minimal tillage, cover cropping, crop rotations, companion planting, rotational grazing. All of these habits are to maximizing soil cover and maintaining actively growing roots to support soil microbes.

The problem with fertilizers that simply nourish the plant is that it encourages shallow roots: if the liquid is applied to the top of the soil, roots don’t have to dig far nor do they create much of symbiosis with the soil to get the nutrients they need to grow.

Deep roots = better soil structure, and better chemistry, which invites more biology, more resilience, healthier soil. Personally I don’t see how conventional fertilizers (even if organic) have any place when it comes to long term goals of a holistically managed land.

Ideally, the cow pats, followed by grazing chickens are what would fertilize soil in pastures. Techniques like composting helps nourish the soil in market gardens, which actively feeds the soil fertility, which in turn will nourish the plant. When we go straight for liquid fertilizers, it doesn’t take into account soil health, it’s bypassing the cycle of living soil.

ORGANIC METHODS OF DEALING WITH PESTS FOR FRUIT & VEGGIES?

This is a massive topic, that goes beyond my scope of knowledge. Like the climate question, there are so so many variables here. From what I understand, though, dealing with a pest problem with added inputs like sprays doesn’t address the underlying ecosystem imbalance that brought upon the pests in the first place. You see, when nature is in balance— ‘pests’ don’t exist, neither do ‘weeds’. Both are indicators, information about what the farmer can be doing better. You can look up ‘weeds as indicators’ and dive down that rabbit hole.

Note also, that if nothing is trying to eat your food: it’s probably not food. So congratulations, you’re growing food! Growing food in an urban setting will definitely bring on animals and other visitors who want in on your food supply— for that I suggest getting involved with your community (co-ops, community gardens) and coming up with a plan as a group. I don’t have ‘the solution’, every garden has its own trials and tribulations that you as the holistic manager of your soil has to resolve. There’s no one linear answer to a gardens problem, but by getting involved with the community (or the online community! there’s great Facebook groups), you can stand on shoulders of giants who have experience in your microclimate.

HOW CAN I LEARN AND CONTRIBUTE?

I recently spent some time with Sasha, a farmer at Dunloe Park, the regenerative cattle farm in Sleepy Hollow NSW. I asked her this question, and her answer was to reconnect with your food, with the farmers, with the land. To actually visit the farms and have an awareness of their practices. To ask questions, to get involved.

Personally I think that this awareness and participation is where to start, and from there the way YOU can best participate will show itself. Whether it simply be making better food choices, supporting these more local and regenerative farms, or whether that means actually getting involved physically (working for, or volunteering) with regenerative farms or the movement in some way.

Personally, I have been involved in the ‘health’ industry for over a decade. Working in gyms, health food stores, at the farmer’s markets, in juice bars: I’ve always had the drive to immerse myself in the very broad category of the health industry. This led to my valuing of organic food, which led me to volunteer on an organic farm in Maui, Hawaii for 3 months.

After my writing career took off, I kept being called back to work directly with the land, and so I found Conscious Grounds, a regenerative earth school and working farm located in Byron Bay, Australia (where I currently live). I spend at least one day a week there now, and have completely dedicated my writing path to this world. Health, to me, is rooted in soil health. There is no divorcing the human from the land we walk on, from the ecosystem we live in. The more I learn about regenerative agriculture the more committed I am to spending my spare time volunteering for, and working in the direction of this movement. Shedding light on the topic, learning more myself.

So the best thing you can do, in my opinion, is get informed. Knowledge is power. Once you understand the why, the how will show itself. Once you feel the visceral calling and innate knowing, there’s just no looking back. You will know what you can do.

..OH! And grow something! No matter where you live, no matter how big or small your space, whether you do it at home or in a community garden: you can grow something. Be it a full blown veggie garden, a fruit tree, or a simple herb garden: reconnect with your food. Seeing the true magic that it turning something from a seed into a food ignites that primal understanding inside of you. Grow something.

Spending one full day immersed on a regenerative farm per week has reconnected me with the land and opened my eyes to the passion I have for this subject. (Image of me shovelling cow poop as the sun rises, one of my favourite morning duties. Living meditation).

Mornings on the farm, the best.

FARMER-LED TABLES

This is a concept I first heard of reading Dan Barber’s The Third Plate. You’ve no doubt heard to the concept of farm to table, but what Dan points out so eloquently in his book is that the farm-to-table model is still led by consumer demands. We like the idea of reconnecting with our food (especially in a rustic setting…) but we still have these deeply embedded preferences, that lead our palate, and ultimately dictate how we spend our money.

These non-budging preferences for carrots year-round, for conventional cuts of meat (chicken breast, ribeye or sirloin steaks): it shapes the menu, which means unsustainable practices on the farming side. A cow is not made up of 300 sirloin steaks. They have tongues, livers, cheeks, some cuts are tougher and require different preparation. And then there’s the carcass, the joints and bones. Ironically, a healthy person needs all the cow (nose-to-tail) to thrive, and consuming only muscle meat can actually lead to an amino acid imbalance.

But I digress: the key here is that a large part of regen ag is letting the farmer dictate what is most suited to grow on their land, in that microclimate. We have become so spoilt when it comes to choice that many of us have absolutely no idea what’s truly “in season”. In season actually changes from state (or province) to state. It changes based on microclimates, based on the nature of that farms soil and resources. When we demand carrots year-round, for example, farmers are forced to grow something that may not actually be the most suited to their land.

Farmer-led-tables unfortunately requires consumers to give farmers permission to do so. Since there’s so much competition, if a farmer decides to farm truly sustainably and provide the limited crops that are most suited to his or her land: odds are you will just go to the next stall, or to the large grocery chain and just get your damn carrots. So take it upon yourself to shed your gluttony for variety, and start honouring the farmer and your land. Your ecosystem. Ask the farmers what crops they would naturally grow at this time of year, irrelevant of demand. What choices can you make food-wise to support their sustainable farming practices.

SUSTAINABLE EATING, IN ACTION

The 5 photos above are a great representation of what farmer-led-tables can look like. At the farm I volunteer at, we are fed food that comes almost exclusively from food grown on the property. For the past months, that has been a lot of eggs, greens (no, not your typical ‘lettuce’), and cassava. The amazing kitchen team ferments and pickles things like radishes, they get creative making fresh kombucha using fruits on the property, they turn cassava into sweet or savory dishes. Farmer-led tables don’t have to be boring, but they do require adapting to a more limited range of foods that rotate seasonally. This is what sustainability looks like in action.

Here is a talk by Dan Barber, on the subject of his book and this shift to farmer-led-tables:

QUESTIONS TO ASK

At the farmers market:

Does this produce/ meat all come from one farm? Do you work on the farm? What is your relationship to the farm?

What are farming practices like? Do you use any herbicides or pesticides?

Do they use artificial fertilizer— if so, why? Which ones?

Are there animals on the property, how are they used?

Do they use rotational grazing principles? Why or why not? Tell me more about them.

Where is the farm, can I visit it?

What is actually in season, what grows abundantly on the farm right now, what should I be buying to support your most sustainable practices?

When buying meat at the farmers market, also ask the questions below:

At the butcher:

What are the farming practices of the meat served here?

Does it all come from one farm (there’s basically no way the answer will be yes for the whole shop, but inquire about the specific type of meat, i.e. does all the beef come from one specific farm)

Is this meat pasture-raised? What does pasture-raised mean to you?

Is it certified organic, why or why not?

Is the ruminant meat grass-fed AND finished? *don’t take their word for it. Always follow up by asking for the farm’s name, and telling the butcher you will also be following up with the farm directly.*

When following up with the farm directly, ask all the questions above (the farmer’s market questions).

At the grocery store:

So at the grocery store, you are the most disconnected from your food— because for the most part the people working there just stock the shelves. This kind of depends on where you are in the world, some countries have more awareness of their produce and products but for the most part, these people are salesmen and women who stock the shelves. If you ask them where it’s from, they go to look at the order sheet and point at a name or location.

So when it comes to grocery store-bought food, you will probably have to look at the company name (or ask them if it’s produced), and then go home and shop online or call them directly. If grocery-store bought goods are your only option, make sure you do this. Get as close as possible to the source of your food, and then ask the questions aforementioned (for butchers and for farmers markets).

“We need to be uncompromising in our quest for the best.”

— MICHAEL BESANCON, CEO BESANCON GROUP

DIVE DEEPER

Here are some resources, for those so inclined, to dive deeper into this absolutely life changing subject. If you made it this far, congrats: you give a shit. I think you’re probably as hooked as I am on the fact that regenerative agriculture is the solution of essentially every problem facing man kind at the moment. How exciting, don’t you think? So dive in, go deep. Share your passion with those around you, do it from a place of love. Together we can heal the soil, and ourselves. As above, so below.